Up until last month, people were still asked to submit documents to the government using the outdated storage devices, with more than 1,000 regulations requiring their use.

But these rules have now finally been scrapped, said Digital Minister Taro Kono.

In 2021, Mr Kono had “declared war” on floppy disks. On Wednesday, almost three years later, he announced: “We have won the war on floppy disks!”

Mr Kano has made it his goal to eliminate old technology since he was appointed to the job. He had earlier also said he would “get rid of the fax machine”.

Once seen as a tech powerhouse, Japan has in recent years lagged in the global wave of digital transformation because of a deep resistance to change.

For instance, workplaces have continued to favour fax machines over emails – earlier plans to remove these machines from government offices were scrapped because of pushback.

The announcement was widely-discussed on Japanese social media, with one user on X, formerly known as Twitter, calling floppy disks a “symbol of an anachronistic administration”.

“The government still uses floppy disks? That’s so outdated… I guess they’re just full of old people,” read another comment on X.

Others comments were more nostalgic. “I wonder if floppy disks will start appearing on auction sites,” one user wrote.

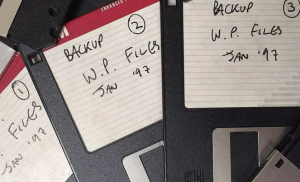

Created in the 1960s, the square-shaped devices fell out of fashion in the 1990s as more efficient storage solutions were invented.

A three-and-a-half inch floppy disk could accommodate up to just 1.44MB of data. More than 22,000 such disks would be needed to replicate a memory stick storing 32GB of information.

Sony, the last manufacturer of the disks, ended its production in 2011.

As part of its belated campaign to digitise its bureaucracy, Japan launched a Digital Agency in September 2021, which Mr Kono leads.

But Japan’s efforts to digitise may be easier said than done.

Many Japan businesses still require official documents to be endorsed using carved personal stamps called hanko, despite the government’s efforts to phase them out.

People are moving away from those stamps at a “glacial pace”, said local newspaper The Japan Times.

And it was not until 2019 that the country’s last pager provider closed its service, with the final private subscriber explaining that it was the preferred method of communication for his elderly mother.

BBC