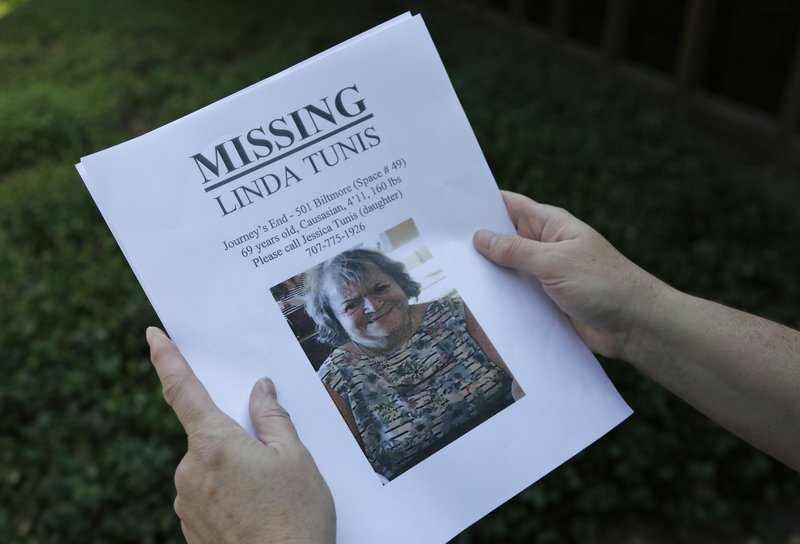

SANTA ROSA, Calif. (AP) — A frantic Jessica Tunis had been calling hospitals and posting on social media when her family’s search ended up back at the charred ruins of her mother’s Santa Rosa house on Wednesday, looking for clues in the debris as to where she might be.

Linda Tunis had last called Jessica from her burning house at Journey’s End mobile home park early Monday, saying “I’m going to die” before the phone went dead. Her home was destroyed in wildfires that swept Northern California’s wine country

“She’s spunky, she’s sweet, she loves bingo and she loves the beach, she loves her family,” said Jessica Tunis, crying. “Please help me find her. I need her back. I don’t want to lose my mom.”

Hours later Tunis texted an AP reporter to say that her brother, Robert, had found her mother’s remains among the debris. Authorities put the remains of the 69-year-old woman in a small white plastic bag and strapped it to a gurney before taking it away.

Hundreds of people remained unaccounted for Wednesday as friends and relatives desperately checked hospitals and shelters and pleaded on social media for help finding loved ones missing amid California’s wildfires.

“She’s spunky, she’s sweet, she loves bingo and she loves the beach, she loves her family,” said Jessica Tunis, crying. “Please help me find her. I need her back. I don’t want to lose my mom.”

Hours later Tunis texted an AP reporter to say that her brother, Robert, had found her mother’s remains among the debris. Authorities put the remains of the 69-year-old woman in a small white plastic bag and strapped it to a gurney before taking it away.

Hundreds of people remained unaccounted for Wednesday as friends and relatives desperately checked hospitals and shelters and pleaded on social media for help finding loved ones missing amid California’s wildfires.

As of Wednesday, 22 wildfires were burning in Northern California, up from 17 the day before. The blazes killed about two dozen people and destroyed an estimated 3,500 homes and businesses, many of them in California’s wine country.

How many people were missing was unclear, and officials said the lists could include duplicated names and people who are safe but haven’t told anyone, whether because of the general confusion or because cellphone service is out across wide areas.

“We get calls and people searching for lost folks and they’re not lost, they’re just staying with somebody and we don’t know where it is,” said Napa County Supervisor Brad Wagenknecht.

With many fires still raging out of control, authorities said locating the missing was not their top priority.

Sonoma County Sheriff Robert Giordano put the number of people unaccounted for in the hard-hit county at 285 and said officers were starting limited searches in the “cold zones” they could reach.

“We can only get so many places and we have only so many people to work on so many things,” he said. “When you are working on evacuations, those are our first priority in resources.”

As a result, many people turned to social media, posting pleas such as “Looking for my Grandpa Robert,” ″We are looking for our mother Norma” or “I can’t find my mom.” It is an increasingly familiar practice that was seen after Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria and the Las Vegas massacre.

A sobbing Rachael Ingram searched shelters and called hospitals to try to find her friend Mike Grabow, whose home in Santa Rosa was destroyed. She plastered social media with photos of the bearded man as she drove up and down Highway 101 in her pickup.

Privacy rules, she said, prevented shelters from releasing information.

“You can only really leave notes and just try and send essentially a message in a bottle,” she said.

Ingram said she hopes Grabow is simply without a phone or cell service.

“I’ve heard stories of people being relocated to San Francisco and Oakland. I’m hoping for something like that,” she said. “We’re hearing the worst and expecting the best.”

Grabow’s name was among dozens written on a dry erase board at the Finley Community Center in Santa Rosa, which the Red Cross had turned into an evacuation center with dormitories, cold showers and three meals a day. Dozens of evacuees hung about, waiting for word for when they could return to their homes.

Debbie Short, an evacuee staying at the Finley Center, was a good example of a person listed as missing who was not. She was walking past the dry erase board when she noticed her name on the board, likely because a friend had been looking for her.

A Red Cross volunteer erased her name off the board.

Frances Dinkelspiel, a journalist in Berkeley, turned to social media for help finding her stepbrother Jim Conley after tweeting authorities and getting little help. But it was a round of telephone calls that ultimately led her to him.

A Santa Rosa hospital initially said it had no record of him, but when the family tried again, it was told he had been transferred elsewhere with serious burns.

It was a frustrating experience, Dinkelspiel said, but “I’m glad he’s in a hospital and isn’t lying injured on the side of the road.”

___

This story has been corrected to show that people used social media to search for missing after Hurricane Irma, not Rita.

___

AP