By ceding control of its borders and airspace to various foreign actors, the regime has essentially resigned itself to a limited but potentially durable existence for the long term.

In an official sense, at least, the situation on Syria’s borders has hardly changed at all over the past couple years. The Western agenda still excluded any international solution comparable to what the Dayton Accords established in the former Yugoslavia. Russia and its partners in the “Astana process,” Iran and Turkey, oppose any formal efforts to partition the country or cement the existence of a separate Kurdish entity in the north. Moreover, the problems that followed the partition of Sudan have given Western policymakers serious doubts about the viability of such a solution for Syria. Yet none of these abortive international possibilities has prevented external powers from informally dividing the country into multiple zones of influence and unilaterally controlling most of its borders, thus depriving the Assad regime of a major instrument of sovereignty.

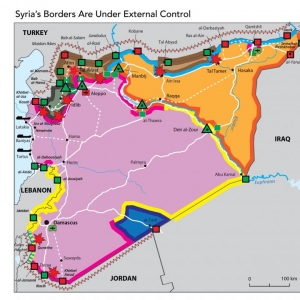

Open imageiconMap “Syria’s Borders Are Under External Control”

Borders Tell the True Sovereignty Story

The regime’s counterinsurgency strategy has certainly borne fruit inside the country. Bashar al-Assad’s forces now control two-thirds of Syria’s territory, including all six main cities (Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, Latakia, Tartus, Deraa, and Deir al-Zour), as well as 12 million people out of an estimated resident population of 17 million (another 7 million Syrians are still living abroad as refugees). This is a complete turnaround from the low-water level of spring 2013, when Assad’s forces controlled only a fifth of the country.

Yet borders are the sovereignty symbol par excellence, and the regime’s scorecard remains nearly blank on that front. The Syrian army controls only 15 percent of the country’s international land borders; the rest are divided between foreign actors.

The West and South: Illusory Regime Control

Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed Shia militias currently control around 20 percent of the country’s borders. Although Syrian customs authorities are officially in charge of the crossings with Iraq (Abu Kamal), Jordan (Nasib), and Lebanon (al-Arida, Jdeidat, al-Jousiyah, and al-Dabousiyah), the reality is that true control lies elsewhere. The Lebanese border is occupied by Hezbollah, which has established bases on the Syrian side (Zabadani, al-Qusayr) from which it dominates the Qalamoun mountainous region. Similarly, Iraqi Shia militias manage both sides of their border from Abu Kamal to al-Tanf. The stranglehold of pro-Iranian forces also extends to several of Syria’s military airports, which often serve as receptacles for Iranian weapons destined for Hezbollah and the Golan Heights frontline with Israel. This situation reveals Syria’s complete integration into the Iranian axis.

Open imageiconMap “The Iranian Axis: Ideology and Geopolitics”

After the reconquest of the south in June 2018, the Syrian army returned to the Jordanian border and reopened the Nasib crossing with great fanfare. Yet traffic remains very limited today, and the army’s presence in Deraa province is superficial. To quickly tamp down growing resistance in the area, the regime was forced to sign reconciliation agreements brokered by Russia, leaving local rebel factions with temporary autonomy and the right to keep light weapons. Ex-rebels have also maintained strong cross-border links via the Jordanian frontier, giving them a potential source of logistical support in the event of a new conflict (and very lucrative smuggling income in the meantime).

The North: Turkish Proxies and Russian Troops

In 2013, Turkey began construction of a border wall in the Qamishli area, a stronghold of the Syrian Kurds; it has since extended this barrier along the entire northern frontier. One objective was to prevent infiltration: first by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a group that Ankara regards as its chief domestic enemy and the parent organization of the Kurdish factions that control large parts of north Syria; and later by the Islamic State, after a wave of jihadist terrorist attacks rocked Turkey in 2015.

Another objective was to block the flow of additional Syrian refugees into Turkey, where 3.6 million are already being hosted. Individual crossings are still possible via ladders and tunnels, but Turkish police stop most such migrants and bluntly send them back to Syria.

In effect, the only portion of the northern border under Assad’s control is the Kasab crossing north of Latakia, and even that has been closed on the Turkish side since 2012. From Kasab to the far eastern border, the Syrian side of the frontier is successively controlled as follows:

By pro-Turkish Turkmen rebels until Khirbet al-Joz

By the Sunni Arab jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham between Jisr al-Shughour and Bab al-Hawa

By pro-Turkish rebels of the so-called “Syrian National Army” (SNA) up to the Euphrates River

By the Russian army and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) around Kobane

By the SNA between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain

By the Russian army and SDF from Ras al-Ain to the Tigris River

In October 2019, Turkey launched a cross-border offensive in the north, spurring American forces to withdraw from most of the territory controlled by the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). Russia then took control of the contact zones between the SDF, Turkey, and its SNA auxiliaries in accordance with the ceasefire agreement concluded in Sochi that same month. Russian-Turkish patrols replaced U.S.-Turkish patrols on these contact lines to ensure that the SDF withdrew from the Turkish border area. Although Assad’s forces have been asked to deploy a few hundred troops along that frontier, their presence is merely symbolic. Russian patrols have since ventured further east, trying to set up a post at al-Malikiyah (Derik in Kurdish) and take control of the crossing with Iraq at Semalka/Peshkhabur, the only land supply route available to American troops in northeast Syria.

Down to One Crossing

All of the northern crossings into Turkey remain closed, and the border wall blocks smuggling activities. This makes Semalka/Peshkhabur the only international window open to the AANES. On the Iraqi side of Syria’s eastern border, Shia militias have been in charge of most areas since fall 2017, when the Kurdistan Regional Government lost control over disputed territory between Kirkuk and Sinjar. Crucially, though, this lost territory did not include Peshkhabur. The SDF control the Syrian side of the border with the support of U.S. troops, but Iranian proxies have prohibited them and other actors from using any other crossing points, partly with the help of Russian diplomatic cooperation.

For instance, the official al-Yarubiya border crossing has been closed to UN humanitarian aid ever since Russia vetoed its renewal at the Security Council in December 2019. Another consequence of this decision is that all UN aid to the entire AANES must first be sent to Damascus before it can be transferred to the northeast.

The Semalka/Peshkhabur crossing is therefore vital to the autonomous region’s political and economic survival, serving as the only entry point for the numerous NGOs who operate there and provide indispensable support to the local population. Yet the Syrian government still considers entry via that crossing to be a crime punishable by up to five years in prison, so NGOs entering the AANES from Iraq must be careful not to conduct any activities in regime-controlled areas. Any NGOs that apply for accreditation with the Syrian Arab Red Crescent in order to operate in regime areas are forced to promise they will cease any activities that involve crossing into the AANES from neighboring countries. The regime’s intransigence on humanitarian issues is likely Assad’s way of trying to reassert at least one aspect of border sovereignty. Meanwhile, Russian patrols are still trying to reach Semalka and test the SDF’s resistance, and Iraqi militias have repeatedly threatened to capture Peshkhabur.

A Future of Limited Sovereignty

In addition to ceding most of its land borders to Russia, Turkey, Iran, and the United States, the Assad regime has also failed to reestablish control over Syria’s skies and territorial waters. Its maritime zones are monitored by forces from Russia’s base in Tartus, and most of its airspace is controlled from the Russian base at Hmeimim. Iran relies on Moscow’s air assets for protection from Israeli strikes—a limited safeguard at best, since Russia does not shield Tehran’s more provocative activities such as transferring missiles to Hezbollah or strengthening its positions in the Golan. For its part, the United States maintains an air corridor between the Khabur River and the Iraqi border, where its last ground troops are located.

Despite its occasional public declarations about reconquering all of Syria, Damascus seems content to submit to this game of foreign powers and hold limited sovereignty over reduced territory for the long term. Even if U.S. troops fully withdraw from the east, the country will remain in the hands of the “Astana triumvirate,” so Assad has little choice in the matter.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

washingtoninstitute