The Houthis resumed their attacks on Ma’rib in mid-February 2021 and almost defeated the government’s forces if it had not been for their resilience; the backing of the tribes; reinforcements from the governorates of Shabwa, Abyan, Taizz and Hodeidah; and the mobilisation of the battle fronts in al-Jawf, Hajjah and Taizz governorates, causing the de-escalation of the attacks and the decline of threat by mid-March 2021.

The Houthis’ resumption of attacks on Ma’rib were linked to constant and critical factors that encouraged if not served as the primary motive behind the resumption. One of the most prominent of these were the transformation of Ma’rib into a military, economic and political headquarters for the internationally-recognised government in place of Sana’a, which is now controlled by the Houthis, and the port city of Aden, which is controlled by the separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC), although the government is stationed there in compliance with the 2019 Riyadh Agreement.

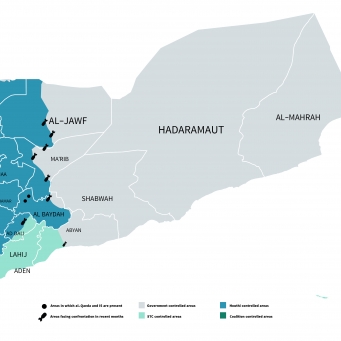

At the military level, the Supreme Command of the Yemeni Armed Forces is stationed in Ma’rib. Furthermore, the geographic proximity of Ma’rib to Sana’a poses a threat to the Houthis’ political stronghold. This pushed the Houthis to seek control of it, leading to consequences including the disruption of the arrangement of the first defence of the governorates of Shabwa and Hadramawt, which are located along the Indian Ocean and have ports and oil and gas fields.

Certainly, the existence of oil and gas fields in Ma’rib, and its control of the road network between Shabwa, Hadramawt and Al-Mahra that leads to Oman and Saudi Arabia, remain a constant and delaying motive for Houthi control of Ma’rib since they seized Sana’a in 2014. This is because control of Ma’rib entails abundant financial resources and returns from commercial activity resulting from population density (about one million people), and what could result from attracting capital to it in the future.

In the context of the pressing factors of escalation, the field progress that the Houthis made in the past 14 months, their seizure of Sana’a and al-Bayda governorates, and their cutting off of vast areas of al-Jawf and Ma’rib governorates is underscored. These factors tempted them to attempt to reach the city of Ma’rib in light of the defence vacuum caused by the withdrawal of the coalition’s strategic air defences from Ma’rib in the face of their missile and unmanned aircraft attacks and the decline of the role of the coalition’s aircraft at the start of 2021.

The Houthis’ ground, ballistic missile and unmanned aircraft attacks on Ma’rib, al-Jawf, Taizz and Hajjah as well as their attacks on the Saudi strategic interests reveal that their military capabilities are better than before and better than those of the internationally-recognised government, especially those facing them at these fronts.

Although the Houthis did not achieve the victory they were expecting from the escalation in Ma’rib, their insistence on appearing as the internally stronger party gave them the ability to influence externally through successive attacks with unmanned aircraft and ballistic missiles on Saudi strategic interests. This had strong resonance with those calling for the end of the war, especially the United States and Britain, causing them to double pressure on Saudi Arabia to take more flexible positions towards the Houthis and launch its peace initiative.

The expected scenarios of escalation in Ma’rib, however, are connected to the Houthis’ intentions towards it. The first of these scenarios is based on the concurrence of negotiations and military field progress. The second scenario, which is more likely, depends on waiting in order to rebuild power by exploiting all the fruits gained from any peace process and taking advantage of the critical transformations arising from the internationally-recognised government.

/studies.aljazeera.net