GANGNEUNG, South Korea (AP) — South Korean officials have ruled out turning a state-of-the-art Olympic skating arena into a giant seafood freezer. Other than that, not much is certain about the country’s post-Winter Games plans for a host of expensive venues.

As officials prepare for the games in and around the small mountain town of Pyeongchang, there are lingering worries over the huge financial burden facing one of the nation’s poorest regions. Local officials hope that the Games will provide a badly needed economic boost by marking the area as a world-class tourist destination.

But past experience shows that hosts who justified their Olympics with expectations of financial windfalls were often left deeply disappointed when the fanfare ended.

This isn’t lost on Gangwon province, which governs Pyeongchang and nearby Gangneung, a seaside city that will host Olympic skating and hockey events. Officials there are trying hard to persuade the national government to pay to maintain new stadiums that will have little use once the athletes leave. Seoul, however, is so far balking at the idea.

The Olympics, which begin Feb. 9, will cost South Korea about 14 trillion won ($12.9 billion), much more than the 8 to 9 trillion won ($7 to 8 billion) the country projected as the overall cost when Pyeongchang won the bid in 2011.

Worries over costs have cast a shadow over the games among residents long frustrated with what they say were decades of neglect in a region that doesn’t have much going on other than domestic tourism and fisheries.

“What good will a nicely managed global event really do for residents when we are struggling so much to make ends meet?” said Lee Do-sung, a Gangneung restaurant owner. “What will the games even leave? Maybe only debt.”

___

TEARING THINGS DOWN

The atmosphere was starkly different three decades ago when grand preparations for the 1988 Seoul Summer Games essentially shaped the capital into the modern metropolis it is today.

A massive sports complex and huge public parks emerged alongside the city’s Han River. Next came new highways, bridges and subway lines. Forests of high-rise buildings rose above the bulldozed ruins of old commercial districts and slums.

The legacy of the country’s second Olympics will be less clear. In a country that cares much less now about the recognition that large sporting events bring, it will potentially be remembered more for things dismantled than built.

But past experience shows that hosts who justified their Olympics with expectations of financial windfalls were often left deeply disappointed when the fanfare ended.

This isn’t lost on Gangwon province, which governs Pyeongchang and nearby Gangneung, a seaside city that will host Olympic skating and hockey events. Officials there are trying hard to persuade the national government to pay to maintain new stadiums that will have little use once the athletes leave. Seoul, however, is so far balking at the idea.

The Olympics, which begin Feb. 9, will cost South Korea about 14 trillion won ($12.9 billion), much more than the 8 to 9 trillion won ($7 to 8 billion) the country projected as the overall cost when Pyeongchang won the bid in 2011.

Worries over costs have cast a shadow over the games among residents long frustrated with what they say were decades of neglect in a region that doesn’t have much going on other than domestic tourism and fisheries.

“What good will a nicely managed global event really do for residents when we are struggling so much to make ends meet?” said Lee Do-sung, a Gangneung restaurant owner. “What will the games even leave? Maybe only debt.”

___

TEARING THINGS DOWN

The atmosphere was starkly different three decades ago when grand preparations for the 1988 Seoul Summer Games essentially shaped the capital into the modern metropolis it is today.

A massive sports complex and huge public parks emerged alongside the city’s Han River. Next came new highways, bridges and subway lines. Forests of high-rise buildings rose above the bulldozed ruins of old commercial districts and slums.

The legacy of the country’s second Olympics will be less clear. In a country that cares much less now about the recognition that large sporting events bring, it will potentially be remembered more for things dismantled than built.

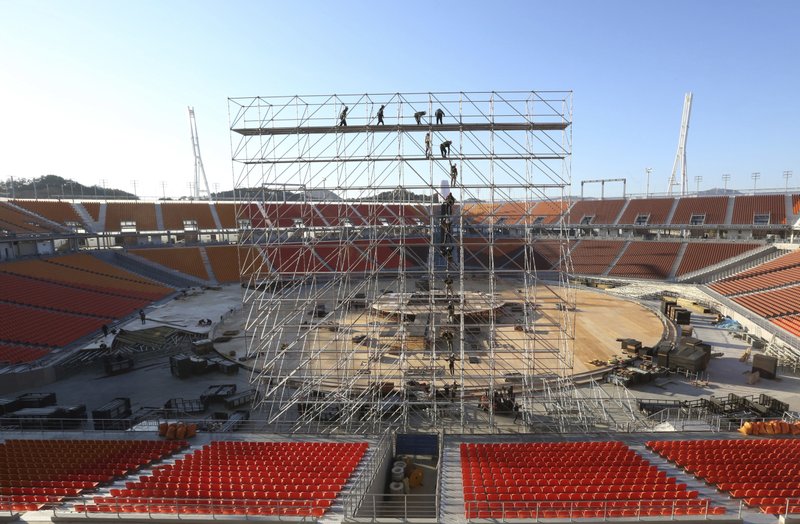

Pyeongchang’s picturesque Olympic Stadium — a pentagonal 35,000-seat arena that sits in a county of 40,000 people — will only be used for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympics and Paralympics before workers tear it down.

A scenic downhill course in nearby Jeongseon will also be demolished after the games to restore the area to its natural state. Fierce criticism by environmentalists over the venue being built on a pristine forest sacred to locals caused construction delays that nearly forced pre-Olympic test events to be postponed.

Gangwon officials want the national government to share costs for rebuilding the forest, which could be as much as 102 billion won ($95 million).

___

NO FISH

Despite more than a decade of planning, Gangwon remains unsure what to do with the Olympic facilities it will keep.

Winter sports facilities are often harder to maintain than summer ones because of the higher costs for maintaining ice and snow and the usually smaller number of people they attract. That’s especially true in South Korea, which doesn’t have a strong winter sports culture.

Not all ideas are welcome.

Gangwon officials say they never seriously considered a proposal to convert the 8,000-seat Gangneung Oval, the Olympic speed skating venue, into a refrigerated warehouse for seafood. Officials were unwilling to have frozen fish as part of their Olympic legacy.

Gangwon officials also dismissed a theme park developer’s suggestion to make the stadium a gambling venue where people place bets on skating races, citing the country’s strict laws and largely negative view of gambling.

A plan to have the 10,000-capacity Gangneung Hockey Center host a corporate league hockey team fell apart.

Even worse off are Pyeongchang’s bobsleigh track, ski jump hill and the biathlon and cross-country skiing venues, which were built for sports South Koreans are largely uninterested in.

After its final inspection visit in August, the International Olympic Committee warned Pyeongchang’s organizers that they risked creating white elephants from Olympic venues, though it didn’t offer specific suggestions for what to do differently.

Cautionary tales come from Athens, which was left with a slew of abandoned stadiums after the 2004 Summer Games that some say contributed to Greece’s financial meltdown and Nagano, the Japanese town that never got the tourism bump it expected after spending an estimated $10.5 billion for the 1998 Winter Games.

Some Olympic venues have proved to be too costly to maintain. The $100 million luge and bobsled track built in Turin for the 2006 games was later dismantled because of high operating costs. Pyeongchang will be only the second Olympic host to dismantle its ceremonial Olympic Stadium immediately after the games — the 1992 Winter Olympics host Albertville did so as well.

___

‘MONEY-DRINKING HIPPOS’

Gangwon has demanded that the national government in Seoul pay for maintaining at least four Olympic facilities after the Games — the speed skating arena, hockey center, bobsleigh track and ski jump hill. This would save the province about 6 billion won ($5.5 million) a year, according to Park Cheol-sin, a Gangwon official.

But the national government says doing so would be unfair to other South Korean cities that struggled financially after hosting large sports events. Incheon, the indebted 2014 Asian Games host, has a slew of unused stadiums now mocked as “money-drinking hippos.” It would also be a hard sell to taxpayers outside of Gangwon, said Lee Jae-soon, an official from the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

Unlike the 1988 Olympics and the 2002 World Cup, which were brought to South Korea after bids driven by the national government, the provincial government led the bid for the Pyeongchang games and it did so without any commitment from Seoul over footing the bill.

Under current plans, Gangwon will be managing at least six Olympic facilities after the games.

These facilities will create a 9.2 billion won ($8.5 million) deficit for the province every year, a sizable burden for a quickly-aging region that had the lowest income level among South Korean provinces in 2013, according to the Korea Industrial Strategy Institute, which was commissioned by Gangwon to analyze costs.

Hong Jin-won, a Gangneung resident and activist who has been monitoring Olympic preparations for years, said the real deficit could be even bigger. The institute’s calculation is based on assumptions that each facility would generate at least moderate levels of income, which Hong says is no sure thing.

He said that could mean welfare spending gets slashed to help make up the lack of money.

South Korea, a rapidly-aging country with a worsening job market and widening rich-poor gap, has by far the highest elderly poverty rate among rich nations, according to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development figures.

If Seoul doesn’t pay for the Olympic facilities, and Gangwon can’t turn them into cultural or leisure facilities, it might make more sense for Gangwon to just tear them down.

Park said the national government must step up because the “Olympics are a national event, not a Gangwon event.”

AP